~by Michael Wilcox

Assistant Director and Program Leader for Community Development / Purdue Extension

Associate Director / North Central Regional Center for Rural Development (NCRCRD)

History tends to repeat itself.

Back in March 2020, we were entering into the unknown. The pandemic was taking hold, and everyone across the globe was trying to determine the appropriate courses of action.

At that time, I wrote: “I have been thinking about the choices we make and the ways in which we conduct ourselves in our community…On the face of it, collaboration seems like a natural state. The problem exists and we need to work together to solve it. As we all know, it isn’t that easy.”

Now, in September 2022, we are confronting countless reminders of how difficult collaboration can be.

Even before March 2020, our stakeholders, and the communities they serve, were constantly faced with choosing how to spend their time. Grant-funded projects, organizational boards, local government initiatives, faith-based activities, non-profit ventures, and countless other opportunities. Alas, in rural areas and urban neighborhoods across Indiana, it is the “same ten people” who often invest their time, talent, and treasure’ in these endeavors. These lifts are heavy, and we need to engage more people actively.

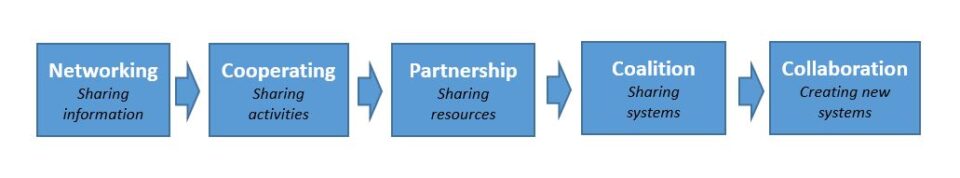

As we come out of the pandemic, we are all finding our way into the ‘new normal.’ Given this, we should revisit the engagement model I introduced in March 2020. A better understanding of the levels of engagement and what they entail may help people, and the organizations they serve, create more robust community linkages.

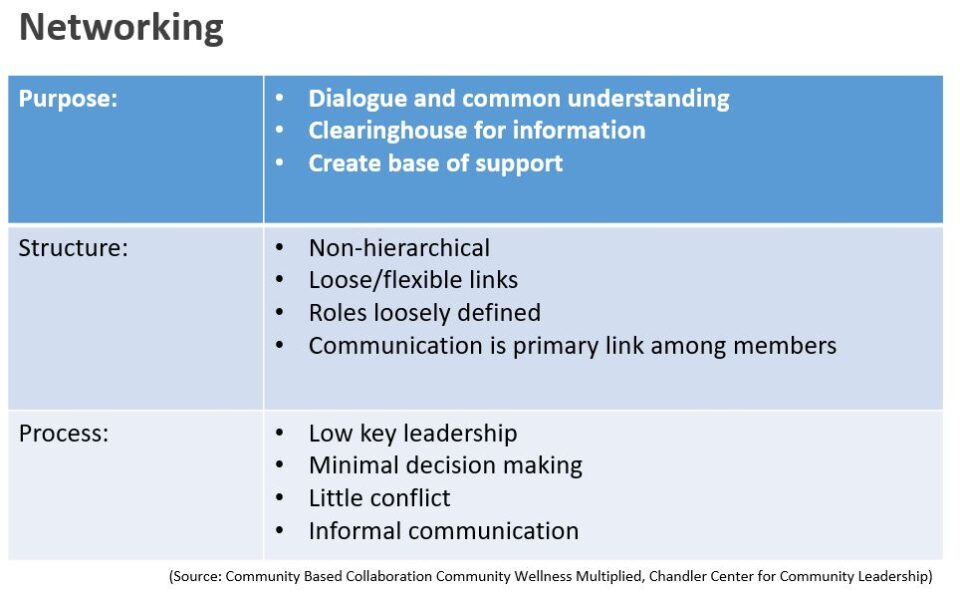

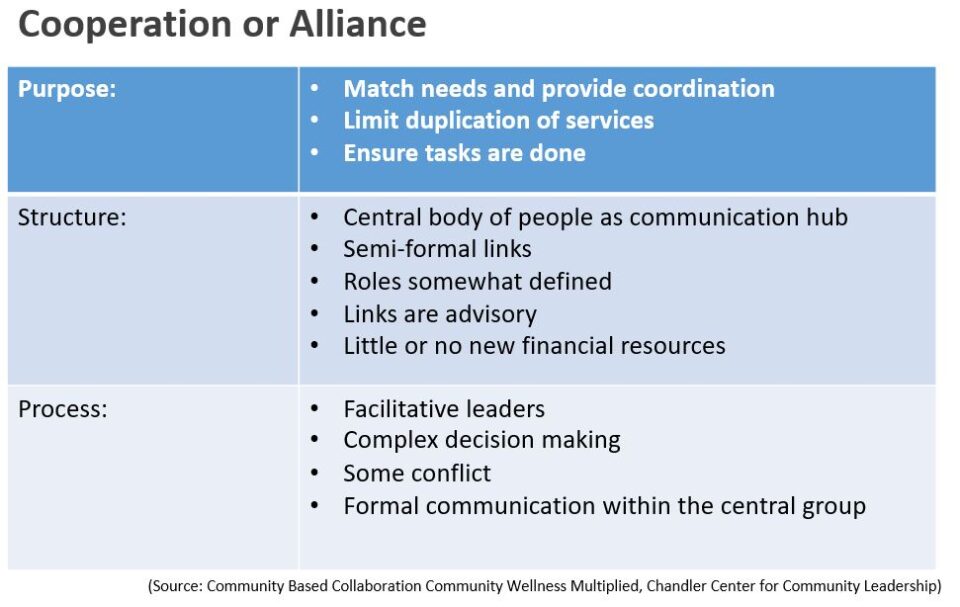

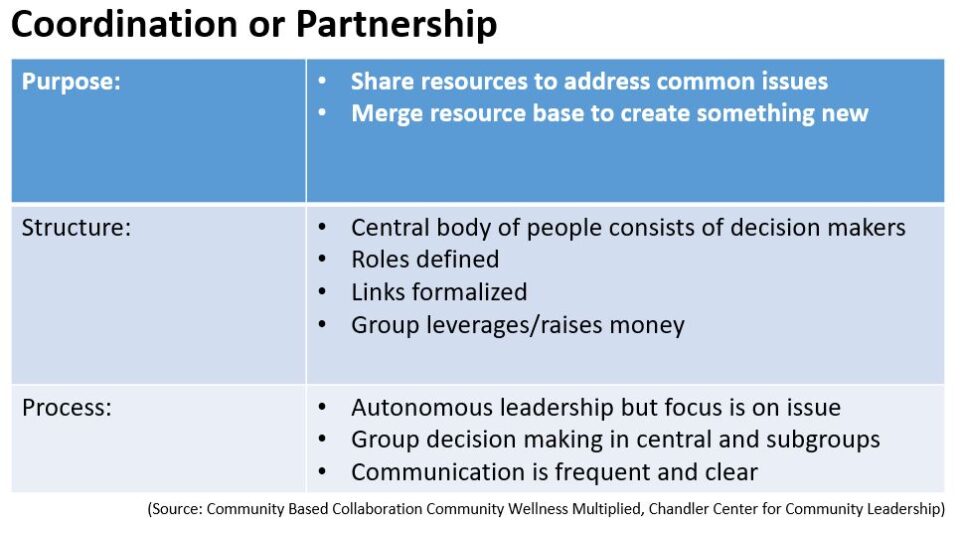

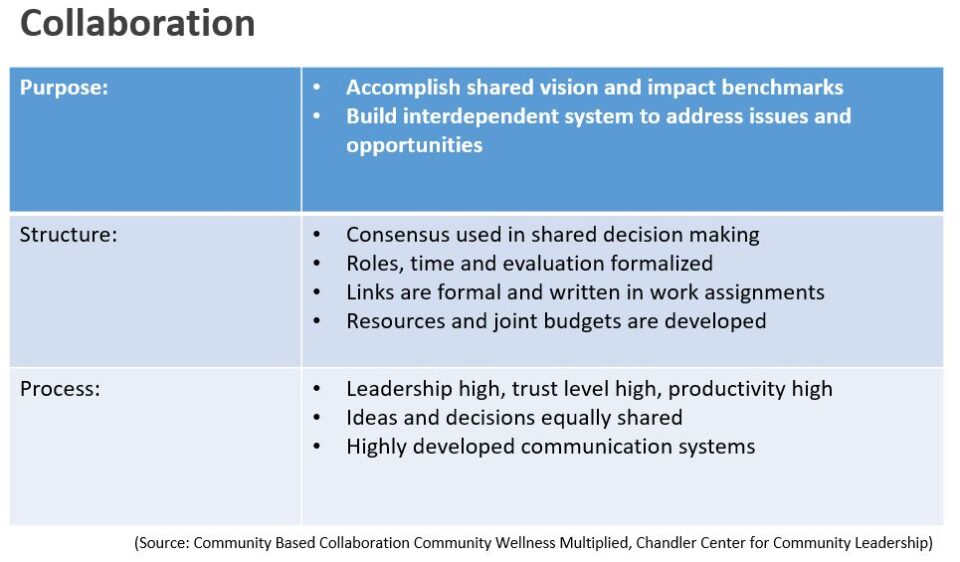

Let’s begin in the same place as before, Teresa Hogue’s “Community Based Collaboration Community Wellness Multiplied.” Published in the early 1990s, this (now) hard-to-find but often cited work provides an easy-to-understand framework of different levels of community linkages, highlighting their purpose, structure, and the processes involved.

Underpinning this model are the following fundamental concepts that people and organizations have:

- Understanding of how their expertise and skill fit into the big picture and willingness to accept the challenge to make significant contributions

- Belief in the community and in its desire to produce the best possible services

- Recognition of their talents, experience, and contributions

- Acceptance that diversity in all of its dimensions is an advantage to the community

- Knowledge that each resident and organization is essential to the community

Cultivating mutual understanding, beliefs, recognition, acceptance, and knowledge is the first step toward creating buy-in. Creating genuine buy-in doesn’t involve developing superficial appearances. Buy-in requires opportunities for community members to identify needs and opportunities and to identify potential responses that will address these. Buy-in is a sense of ownership in a concept or project because people feel they have influenced by identifying the need or opportunity and designing a response. In this sense, community development is an act of will.

Buy-in occurs when people clearly understand the intended benefit of the proposed action/initiative/project. However, to be successful, buy-in needs to transform into active engagement. Active engagement is mobilizing individuals and groups to act in a coordinated way and to invest their resources in implementing a plan. Active engagement requires local people to create the vision for the burgeoning community development strategy. And the vision needs to:

- Inspire stakeholders to work together to achieve a common goal

- Engage the creative energies of the community

- Reflect the interests, dreams, and concerns of all community members

- Establish the basis for making critical public choices

- Build on the assets of the community

While creating the vision and the community is becoming actively engaged, individuals and organizations have choices to make. For example, how are we going to interact? What is the purpose of our interaction? What types of processes are we going to employ? Hogue lays this out nicely in a series of tables (see below) highlighting different ways of working together.

In my work, I have found that the current challenge in our communities is a general level of disengagement. As communities emerge from the pandemic, they realize that they are exhausted and disconnected. The same is true for businesses and their employees. This is why we need to start with the basics (understanding, beliefs, recognition, acceptance, and knowledge) and revisit our vision and mission with intention. In doing so, we begin to re-ignite buy-in and foster active engagement.

While reading through the following, consider your role and the organizations you serve. Are you operating at the most effective level? What changes would need to be made for your vision and plan to be successfully implemented? Who isn’t currently at the table, and how might they be linked to your efforts? What is constraining people and organizations from moving through the continuum from networking to collaboration? What is dampening buy-in and active engagement?

By honestly considering and answering these questions, you will be well on your way to believing in the possibility of change, your capacity to succeed, and open to the possible advantages of true collaboration.

NOTE: This article is based on the presentation, “From Networking to Collaboration and Buy-In to Active Engagement,” by Dr. Michael Wilcox and Dr. Lori Garkovich.