We All Come From Somewhere – Part 2

~by Michael Wilcox

Assistant Director and Program Leader for Community Development / Purdue Extension

Associate Director / North Central Regional Center for Rural Development (NCRCRD)

Last month, I offered a glimpse into our Purdue Study Abroad trip to Ireland focused on rural development. Our planned activities exceeded our expectations during the trip, but the unplanned events took us to a whole other level.

In a nutshell, we proved the adage that “home is where the heart is…” However, we also learned that conventional thinking would not help communities achieve their goals.

Here’s what happened…

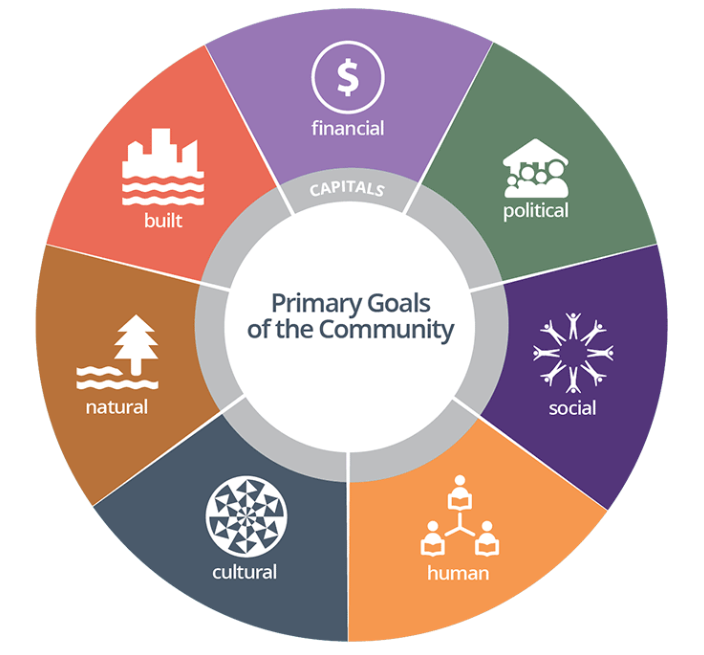

For many Community Development Professionals, the conceptual framework of the Community Capitals undergirds everything we do. While each capital has received attention in the academic literature separately, we bring them together as a functional framework to guide our participatory, asset-based work in communities. I usually refer to the Community Capitals as a “contact lens” through which everyone should examine their community.

We asked our students to choose a capital (from an extended list) to focus on while they were in Ireland. With this approach, each student observed how their selected ‘ingredient’ functioned to foster innovative rural development strategies in Ireland. Here is the list (the first eight are the Community Capitals, and the remainder are taken from the lesser-known PESTLE model):

As I discussed in Part I, Kathleen Lonergan Erickson (University College Dublin) walked us through the innovation process; she noted that it starts with empathy. This connection to our trip theme was coincidental and most welcome.

Kathleen emphasized that while empathy opens the door to understanding people’s needs, one must consider action-oriented solutions. Or, as Kathleen put it, “you must think of needs as verbs, not nouns.” By doing so, you free yourself from conventional thinking and begin to operate in design thinking mode — an approach to problem-solving that prioritizes needs. Hence, being pragmatic is not always the most effective or efficient means to an end.

Armed with these concepts, we finally set out to discover rural Ireland. Our first destination was Athenry and Mountbellew. For those of you that are familiar with Ireland and Irish music, I know you are already humming the tune and singing the lyrics…

“Low lie the fields of Athenry

Where once we watched the small free birds fly

Our love was on the wing we had dreams and songs to sing

It’s so lonely ’round the fields of Athenry”

– “The Fields of Athenry” (RIP Pete St. John)

In Athenry, we met with farmers, scientists, and technicians associated with Newford Beef Farm and Teagasc (pronounced ch-AH-guhsk) as well as the Teagasc Animal & Grassland Research and Innovation Centre. Once again, everyone in our group found something exciting. We were soaking up new knowledge, whether it was grassland management, cutting-edge sheep research, or the innovative extension techniques in use to promote science-based, environmentally-friendly agricultural practices. We were the first visitors since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and everyone was thrilled to be able to learn and share.

Then we set off for Montbellew; that is when the serendipitous magic took over again.

It goes back to my former colleague, Emily Toner. She went on an Irish adventure as a part of her Fulbright-National Geographic Digital Storytelling Fellowship a few years ago. Emily made me fall in love with Irish bogs, though I had never been to one. When we were planning the trip, I found Carrownagappul Bog on the map. It was a must-visit as it is close to Galway and one of Ireland’s largest remaining raised bogs. The fact that it sits near Ireland’s oldest post-secondary agricultural school, Mountbellew Agricultural College, made this an easy choice too.

However, I had no idea that I would meet the force of nature that is Paul Connaughton, Sr., and the dynamic Maura Hannon[i]. Paul is a former member of the Irish Government (a TD – Teachta Dála or Member of Parliament, Political Captial), and Maura is the manager of the Mountbellew Telework Centre. Both are passionate about the Carrownagappul Bog. Maura hosts visitors to the bog and offers them an opportunity to learn more about this unique ecosystem before seeing it for themselves. Paul is a proud Mountbellew native and a former Minister of State for Land Structure and Development (Political Capital). He is also a lifelong turf cutter.

Ireland has a long history of using the “turf” from bogs as fuel to heat homes and cook; it is still used today, primarily in rural Ireland. However, with rising concerns about climate change and health, some have called into question the use of turf as fuel, and recently, the Irish government considered banning it in some areas.

Paul shared a different perspective with us. He understands the role that the Carrownagappul Bog has played in his life and the lives of his neighbors. The impact spans all twelve ‘ingredients’ our students were studying. As Paul and Maura’s perspectives have evolved, they recognize that the days of just extracting turf from the bog are over. Why? Because they began to see the bog as more than a fuel source. They see it as a habitat, a unique ecosystem. They see it as a critical pathway for carbon sequestration. They see it as an outdoor classroom. They see it as a connection to the culture in rural Ireland. They see it as a means of promoting tourism and economic development. And, they recognize that if they don’t act now, they might lose the bog for good. The bog exemplifies the Natural Capital, which has the capacity for significant positive effects if it is stewarded with empathic concern for people and the environment.

Like Kathleen told us at UCD, you need to think of a community’s need as a verb. Paul and Maura want the Mountbellew region to meet its potential sustainably. Before, people needed fuel and thought of the noun, the bog. Now, as Paul so eloquently explains, he sees the bog for what it actually is and recognizes that it needs to be treated respectfully. To our students, he said (at 2:18):

“I have been involved with our place on the bog for over sixty years. And I never saw a thing like I saw in the video [the flora and fauna]. It is there for the eye of the beholder. That is the great thing, knowing those things. They are there if you know what to go looking for and how to go looking for it… When you guys go out into the big, bad world, that is the sort of work you will have to do. Whether it is a bog or whatever else it is, keep asking questions, keep exploring and try to shift the borders of science out a little bit further. That is what YOU are supposed to be after.”

Incredible.

I have been to rural areas all over the globe. This was special. Marie (Dr. Mahon from the National University of Ireland – Galway (NUI-G)) reminded us that such community development efforts are not always successful. Paul and Maura have been successful, in part, because of the networks and support that they have been able to cultivate (Social Capital). This is not a case of glorifying your past as your future dries up (as that guy Bono once sang) but rather reimagining something that had been taken advantage of and turning it into something completely different while respecting aspects from the past. Asset-based, participatory innovation…community development.

From the bog, we visited the Mountbellew Agricultural College (MAC). Interestingly, farmers in Ireland are encouraged to obtain certification from an institution like MAC to pursue a career in farming. Beyond certifications, MAC also offers bachelor’s degrees and serves as a key educational institution in the region. We toured the facilities and met several faculty members. And we learned of their connections to a similar agricultural college in Uganda. As we learned at the Emigration Museum (see Part 1), this was one more example of the Irish acting locally and globally.

While at MAC, it was not lost on us that Principal Dr. Edna Curley was the first female principal of an agricultural college in Ireland. And Martin Mulkerrins (Lecturer) is ranked #3 in Ireland for GAA Handball and won the All-Ireland 4-Wall Singles Championship in 2018. Two exemplary people are living in a Smart Village while tangibly contributing to rural development through the education of people in the region (Human Capital).

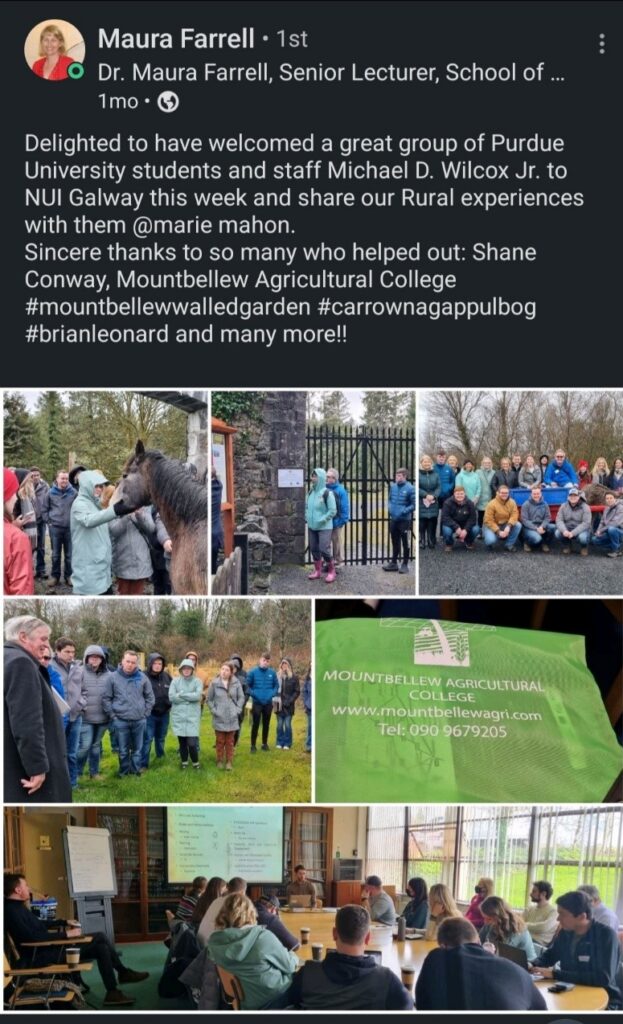

Our last destination was the Walled Garden of Mountbellew. Although we did not know when we chose Mountbellew as a destination, we learned that Maura (Dr. Farrell from NUI-G) lived there. She was only too happy to oblige our request of joining our tour and pulling out all the stops to make it happen (as seen throughout the day). The Walled Garden is one of the last vestiges of the Grattan-Bellew House that was taken down in 1939 (and the stones were repurposed to build roads). The Walled Garden and the adjacent Forge (both Built Capital) now serve as destinations for villagers and tourists alike.

After a fantastic day, we were happy to tour the grounds and pet the four-legged residents (horses!). We felt a kinship with Mountbellew and found out as we were leaving that the village aligns with the color scheme of the Bellew family crest – black and amber – or, as we like to think of it, Purdue black and gold.

The next day we headed to Co. Mayo and Glen Keen Farm. The trip up to the Louisburgh region was a beautiful introduction to the Wild Atlantic Way. Not surprisingly, our welcome mat was based on empathy.

When Mason Gordon was a student at NUI-G, he learned about Glen Keen Farm through a tourism class. Mason, being Mason, called up the owner, Catherine Powers, and they arranged a visit. I’ll dispense with the details, but let’s just say that Catherine and her husband, Jim, made Mason an honorary family member upon his arrival.

Glen Keen Farm provides an interactive and genuine way to learn about Irish culture, farming, and rural development. Catherine and Jim made all of us feel like we were at home. Their passion for the environment and the rural Irish world around them was quite evident.

At this spot, she shared about the Brone Age fort that once stood at this site.

But, as was with this entire trip, we got more than we bargained for…enter Mr. Justin Sammon.

Justin is the CEO of Mayo North East (Oirthuaisceart Mhaigh), an integrated LEADER Partnership company. We thought Justin would greet the group and give a short summary of Mayo North East’s work. Instead, we were treated to very deep thinking on rural development. (Here is a related video so you can hear for yourself). Claire Baney, one of our study abroad participants, explains:

“During our visit to NUI Galway, Drs. Maura Farrell and Shane Conway shared about Ireland’s LEADER program, which began in 1991 as a grant support system specifically designed for community-led development within rural Ireland (Financial Capital). A key tenant of LEADER is to empower communities through a grassroots’ bottom-up’ approach. Residents ideate and implement programs they deem significant for their community; LEADER believes this model yields the most sustainable, effective development results.”

Claire continued, “While government funding and policy can facilitate rural growth, it cannot replace a local community’s drive to revitalize their area and build up their culture. Justin Sammon, CEO of Mayo North East, emphasized the value of this point through all he shared with our group at Glen Keen Farm. Sammon highlighted that Co. Mayo is, by and large, a post-agricultural landscape, meaning the community must be reimagined in new ways, and thus the culture can be reclaimed. To do this, residents must understand their specific history to develop their future – Sammon refers to this focus as ‘sociocultural animation.’[ii] Among Mayo North East’s many programs, they practice sociocultural animation by understanding the historical and present-day significance of migrants, the Travellers (also known as ‘the Tinkers’), women’s groups, indigenous Irish people, and people with disabilities.

Furthermore, Mayo North East has developed purposeful programs to collect and disperse information on Irish anthropology of food, folklore, oral history (even capturing the once ignored stories of those in mother & baby homes), song, and the intersection of ancient Irish knowledge mixed with modern science. Sammon says that “communities are the constructs of their history, and often we ignore this to our peril” (Mayo North East, 2019). His words usher a community’s need for an inclusive and holistic view of culture adjoined with structural change at the political level to continue their growth trajectory.”

Co. Mayo’s efforts in reimagining their future and growth potential.

We were awe-struck. Like Paul from Carrownagappul Bog, Justin reached out to all of our students and let them know that they would be welcome back anytime and that they – as youth – needed to use this experience for something greater. Justin even encouraged us to write grants and formulate research questions that could be tested in his region.

In many rural areas, outsiders are not welcome. Justin turns this notion on its head. He is very open to new people and their new ideas, but these people and their ideas need to recognize the diverse Cultural Capital within the region.

And this is where we circle back to Tamara’s sneaker.

Back in 2021, when we were developing the trip, Marie, Mason, Tamara, and I were trying to determine what rural community we would spend the day in to explore and learn. Kinvara crept into the conversation. It was close to Galway, beautiful, and Marie had access to some of the community’s planning documents. As we were trying to align days with destinations, I had a fateful conversation with Paul Healy, owner of the bus company we had hired. St. Patrick’s Day would take place while we were there, and Paul was angling for a less intensive day as our driver might want to “enjoy what will surely be a ‘social occasion’ after the last two years.” We agreed that experiencing the day in a village would be a memorable experience.

We had no idea.

Immediately after we arrived in Dublin, we received an email from Marie letting us know that she had seen a callout seeking volunteers to help Kinvara put on their first St. Patrick’s Day parade in three years. Without an ounce of hesitation, we let Marie know that the village had fourteen Americans that were completely at their service. If we were going to learn about empathy, we’d better be ready to answer a call for help.

On our way to University College Dublin, we announced to the students that we had volunteered them to help in Kinvara. As Kathleen was wrapping up, one of the students pointed out that Tamara’s shoe coincidentally dons the name…Kinvara. Fate, once again, entered into the equation. Unbeknownst to us, we were already inevitably connected to others and their spaces.

Darragh, our incomparable driver, arrived early (per usual) at our hotel in Galway on the 17th to great anticipation in the air. This was our last day with Darragh, and we weren’t too sure what would be expected of us once we arrived in Kinvara.

When we finally did arrive, we were met by a lovely and quiet seaside village that was just waking up for the day. Marie gave the students a short talk and our students dispersed. They had two or three hours at their disposal to learn as much as they could about how their assigned capital was contributing to Kinvara’s community vitality. Then it would be off to their unknown volunteer assignments.

The students maneuvered around Kinvara like real community development professionals. They did us proud talking with locals, hiking around town, etc., taking advantage of every learning opportunity. Marie, Tamara, and I did the same while enjoying each other’s company, taking in the sights and chatting with the enthusiastic servers at the local coffee shop.

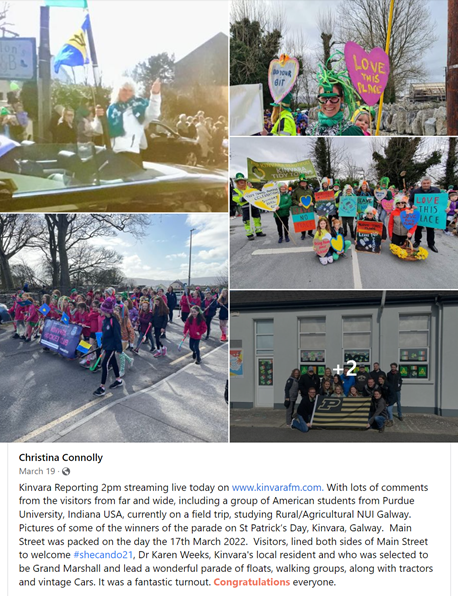

As we regrouped, the village was coming to life. People were assembling in town, having taken all different forms of conveyance. Excitement was growing alongside our collective worry as we still didn’t know where our local contact, Christina Connolly, was to be found. With the information we had on hand, we split the students up and sent them off to ‘do good work.’

They did not disappoint.

One group of students was put in charge of judging floats and another judged decorated storefronts. A third group worked with Kinvara FM. They were handed microphones and served as roving reporters talking to parade-goers throughout the parade. The experience was immersive, genuine, and enthralling. Parents and grandparents back in the States got wind of the events and intently listened as Irish music was played and their children and grandchildren’s voices were heard from thousands of miles away. At least two students reported that tears were shed by family back in the States.

The parade itself was lovely. It had the requisite sports teams, farm implements, and local heroes. But, it also had some deeper messages. Kinvara Tidy Towns marched together, holding signs and chanting “Love This Place, Leave No Trace.” Ukrainian flags were as common as Irish ones. Community pride was evident, and a collective sigh of relief was felt as this was a respite after two years of dealing with a pandemic. We all left Kinvara that day with our hearts swelled with love and admiration for rural Ireland. We want to think that some people in Kinvara felt somewhat the same way about us. We had traveled from far away to commune with them on an important holiday. Many of our group could point to Irish heritage. All of our group brought our American accents. But, in the end, no matter where we originally hailed from, we were all welcomed unconditionally.

Now, we must do more than acknowledge that we all come from somewhere. While ‘home’ may be where the heart is, we must recognize that we have standing where we find ourselves presently. Far too often, people disconnect others from access to political, social and cultural capital due to their status in the community (newcomer, minority, etc.) driven by the dimensions in the Diversity Wheel. If we learned anything in Ireland during our exploration of the intersection between rural development and empathy, it was that this intersection was the critical element for a thriving community. Instead of unwaveringly standing by what has been, play an active role in ideating what could be.

Fintan O’Toole sums it up this way in his recent book on Ireland, We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland, “What is possible now, and was entirely impossible when I was born, is this: to accept the unknown without being so terrified of it that you have to take refuge in fabrications of absolute conviction.”

For rural areas, here in the States, in Ireland, and elsewhere, there is no time better than the present to embrace all community members while working together to find innovative solutions to the wicked problems facing us all. It will take hard work, all twelve ‘ingredients,’ and it must start with empathy.

Thank you to everyone who played a role in making this a life-changing experience for our students and such a rewarding project for Mason, Marie, Tamara, and me. We greatly appreciate every one of you.

_______________________________________

[1] Rest in peace Pat Hannon (Maura’s husband), who passed unexpectedly a few weeks after our departure.

[2] J.A. Simpson explains, “Animation is an egalitarian movement. It seeks to reduce a so-called “culture-gap” between the culturally affluent and other broad sections of society which suffer from “cultural poverty”. Cultural poverty exists when there is a needlessly restricted range of experiences from which the individual may choose. Even though the restriction seems to be self-imposed and a matter of inclination, it is in fact the outcome of centuries of underprivilege, exclusion, and ignorance together with low self-expectation. Poverty of this kind is not merely quantitative. Creative and expressive group experience are of especial value, and an habitual repertoire deficient in these is poverty stricken. Unawareness of the deficiency is a symptom of it.” (pgs 54-55 in Lifelong Education for Adults: An International Handbook, Advances in Education, 1989, Pages 54-57, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-030851-7.50020-5 ).