Childcare: An Economic Development Strategy

Imagine you are a single mom with three kids, ages 2, 5 and 8. You have a “normal” job working 8-5 p.m. with a slightly flexible schedule. Luckily, you have a local childcare provider that is within your budget and 15 miles of work. Most days, your schedule is like clockwork with your drop-off, work, school and pick-up routines. However, your childcare provider suddenly fell quite ill. You don’t have a back-up provider and no family or friends who can be relied on in a pinch. What will you do? Your eight-year-old will be okay with school, but the toddlers go to the childcare provider full-time. Taking time off works on occasion and is a very temporary solution.

Or consider the dual parent household where one travels extensively for work, leaving the other primarily in charge of household affairs. This person has applied for and secured jobs, lined up childcare and had to quit the job due to the childcare provider not being reliable or having less than optimal schedule.

Perhaps in a household, a parent yearns to work, but the cost coupled with limited childcare availability prevents them from even seeking employment. Employment opportunities are plentiful, but the conditions are not right to be able to participate in the local economy.

These and many other stories can be gleaned throughout the state. The bottom line is that working families with children ranging from newborn through middle school heavily depend on childcare, regardless of income level. Employers who employ parents with young children depend on childcare being available for their workers. Local economies benefit from a community having childcare options for existing and potential workers. It’s even better if those childcare options are licensed, accredited and easy to find.

These and many other stories can be gleaned throughout the state. The bottom line is that working families with children ranging from newborn through middle school heavily depend on childcare, regardless of income level. Employers who employ parents with young children depend on childcare being available for their workers. Local economies benefit from a community having childcare options for existing and potential workers. It’s even better if those childcare options are licensed, accredited and easy to find.

Unfortunately, that is not always the reality in Indiana.

Current Childcare Landscape

A report from the Indiana University Public Policy Institute for the Early Learning Indiana estimated the state of Indiana loses nearly $1.1 billion in economic activity every year due to childcare related absenteeism ($580.7 million) and turnover ($519 million). Additional direct costs include disruptions for employers and unrealized potential tax revenue. The losses are not isolated to any particular type of county – both rural and urban counties are impacted by childcare shortages.[i]

In 2018, nearly 20 percent of the state’s population were 14 years old or younger, equating to 1.3 million kids. Of that number, approximately a third are under five years of age, another third are five and nine years old and the final third are 10 to 14 years old.

Digging a little deeper into Census data requires piecing together various datasets to understand the employment situation in households with young children. The 2017 Census data shows that a large share of parents, regardless of dual or single parent household status work (see Table 1).

Table 1: Employment Characteristics of Individuals with Own Children under age 18 in Family, 2017

| Under 6 years | 6 to 17 years old | |

| Living with both parents | 307,407 | 669,830 |

| Both parents in workforce | 59.8% | 67.2% |

| One parent in workforce | 38.9% | 31.1% |

| No parent in workforce | 1.3% | 1.7% |

| Living with one parent | 175,212 | 339,591 |

| One parent in workforce | 79.2% | 82.9% |

| No parent in workforce | 20.8% | 17.1% |

Source: ACS 5-year estimates, Census Bureau

Additional data shows the following:

- Children aged 6 to 12, 67 percent of all their parents work

- 26 percent of children have parents who lack secure employment[1]

- 3 percent of families with related children under 5 years of age were below the poverty level

- 1 percent of families with related children under 18 years of age were below the poverty level

- 400,000 households receive public assistance, 98.5 are families

One data point we lack is the frequency in which families willingly choose to forgo employment to raise their children. Table 1 does show that in dual households with children under the age of 6, 39 percent only had one parent in the labor force. Despite this information, context is lacking that explains willingness or necessity for one parent to manage the household full-time.

Overall, the data points to society’s dependency on childcare due to the sheer number of individuals with children who work. The state has a sizable number of households with young children who have unsecure employment, live below the poverty level and receive public assistance. An argument could be made that some of these individuals could benefit from additional training, education and skill development in order to pursue higher paying occupations. However, if they have children at home – how can they pursue upskilling opportunities without a childcare support system in place?

[1] For children living in single-parent families, this means the resident parent did not work at least 35 hours per week, at least 50 weeks in the 12 months prior to the survey. For children living in married-couple families, this means neither parent worked at least 35 hours per week, at least 50 weeks in the 12 months prior to the survey. Children living with neither parent were listed as not having secure parental employment because those children are likely to be economically vulnerable. Children under age 18 who are householders, spouses of householders, or unmarried partners of householders were excluded from this analysis. This measure is very similar to the measure called “Secure Parental Employment,” used by the Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics in its publication America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being.

Solutions – Perry County, IN Case Study

In many communities, it’s no secret that childcare issues persist. However, the issue gets treated similarly to the hot potato game, verbally passed around with the idea that someone else should do it. Instead of waiting for ‘someone else’, communities need to view childcare as an economic development

strategy. Attention ought to be given to the quantity of childcare options in addition to the quality of such operations.

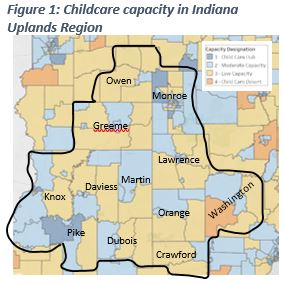

Recently, many of the Indiana Uplands counties completed quality of place and workforce attraction plans. Reviews of those plans found childcare as a pressing issue in seven out of the eleven counties. Local knowledge would argue that childcare issues are present in all of those counties (see Figure 1). In review of the figure, the only places considered a childcare hub (meaning 1.5 childcare spots for every child under age 5) is one Census tract in Pike County and several pockets in Monroe County, a metropolitan area. Other portions of the region have some capacity (light blue), but the overwhelming share indicates low childcare capacity. Low capacity is defined as areas with three children for every childcare spot, but a small number of jobs and relatively low share of children. A desert (located in Washington County, indicates where there are more than three children per spot and a large number of jobs and a high share of children.[i]

Recently, many of the Indiana Uplands counties completed quality of place and workforce attraction plans. Reviews of those plans found childcare as a pressing issue in seven out of the eleven counties. Local knowledge would argue that childcare issues are present in all of those counties (see Figure 1). In review of the figure, the only places considered a childcare hub (meaning 1.5 childcare spots for every child under age 5) is one Census tract in Pike County and several pockets in Monroe County, a metropolitan area. Other portions of the region have some capacity (light blue), but the overwhelming share indicates low childcare capacity. Low capacity is defined as areas with three children for every childcare spot, but a small number of jobs and relatively low share of children. A desert (located in Washington County, indicates where there are more than three children per spot and a large number of jobs and a high share of children.[i]

Perry County, directly south of the Indiana Uplands region, did approach childcare as an economic development challenge. In the spring of 2013, the Perry County Development Corporation, the county’s local ED organization, met with area employers to discuss workforce and barriers to local business growth. Childcare emerged as a central topic of conversation, specifically the lack thereof particularly for employees new to the area without family resources as well as those parents working nontraditional hours. As a result of this meeting, a group was formed to further investigate potential solutions. This group, a mix of representatives from major employers, local school systems, the community at-large, and Perry County Development Corporation staff, began to meet monthly as well as to gather data, conduct surveys, research potential models, attend trainings and visit other communities with childcare facilities. In early 2014, the group officially organized into a board of directors and applied for 501(c)3 status. In January 2015, the organization received its non-profit designation, and fundraising began. The group identified a former childcare center in the community as the optimal location, however funds were needed for renovations in order to bring it up to state licensing standards. In all, nearly $200,000 was donated by local employers. In addition to renovations, these funds were used to purchase all the equipment needed to operate a childcare facility such as cribs, tables, playground equipment, etc.

On August 3, 2015, Perry Preschool & Childcare opened its doors and within a few months, was providing care to over 30 children. The effort was hailed as a tremendous success and a true grass-roots community effort accomplished through the hard work and dedication of a volunteer board of directors which recognized a community need and did not stop until it was met. It was also the first and only state licensed 24/7 childcare facility in the area. The facility continued to operate 24/7 until January 2016 when hours were reduced as very few families were utilizing the extended hours and they were in turn causing an overwhelming financial drain due to state licensing requirements which mandate staff to child ratios. While this was a disappointment to the board of directors who had fully intended to operate a 24/7 facility, daytime enrollment soon reached maximum capacity, so much so that a second toddler room was opened in 2016 and an advanced preschool class was added in 2017. To offset the change from a 24/7 facility, the facility offers wrap-around child care so that working parents do not have to coordinate transportation to and from preschool and child care. The center opens at 4 AM and can offer transportation to all three area schools. The center now serves more than 60 families and there are currently waiting lists for all five classrooms.

In May 2019, Governor Holcomb signed legislation making all Indiana counties eligible to participate in the On My Way Pre-K, a program that awards grants to four-year olds from low income families so that they may have access to high-quality pre-K programs the year before entering kindergarten. Following this, grant funding was made available to early learning centers to expand capacity and elevate quality. In August 2019, Perry Preschool & Child Care received two grants to add an additional preschool room. The Indiana Office of Early Childhood & Out of School Learning awarded the organization more than $23,000 and Early Learning Indiana provided an additional $20,000 in support of this expansion.

Conclusion

Childcare is an often-overlooked component of strong, attractive economically vibrant communities. Working parents, employers and even civic organizations rely on available, safe and quality childcare to keep the local economy humming along. Much effort has been given at the state and regional levels towards assessing the quality of existing licensed childcare facilities, but little attention has been given towards addressing the dearth of childcare options. Childcare must be viewed as an economic development strategy. Examine the existing childcare landscape, determine what gaps exist and what solutions can be pursued. Solutions could range from providing incentives to existing and potential childcare entrepreneurs, support for employers to have in-house childcare facilities or building childcare centers in existing spaces. Each community has their own unique set of assets, thus tailored solutions will be more successful than boilerplate solutions.

Focusing on childcare will likely attract families to the area, raise school readiness levels and increase personal income levels of families who are now able to work. Communities can collaborate together to find meaningful solutions to childcare and Purdue Extension stands at the ready to help.

[i] Littlepage, L. 2018. Lost Opportunities: The Impact of Inadequate Child Care on Indiana’s Workforce & Economy. Indiana University Public Policy Institute. Issue 18-C16.

[ii] Deserts & Hubs: Child Care Access across Indiana – An ELI Story Map. http://datacenter.earlylearningin.org/deserts-hubs.html#Fifth_Sub_Point_2