For Better or For Worse:

Navigating the Uncertainties of Family Business Relationships

BENJAMIN ALLEN

MICHAEL BOEHLJE

As Levi Huffman, general manager of Huffman & Hawbaker Farms, boarded a plane headed to Lincoln, Neb., for the annual North Central Risk Management advisory board meeting, he reflected on the risks in farming. Crop prices have always been volatile, but in the past few years, the markets have been like a roller coaster. And then the drought of 2012 hit, the worst drought since 1988 for his farm. But a recent conversation with a few friends had made him think about some other risks. One had lost the lease on 25 percent of the acreage he farmed to a neighbor who had outbid him on the rent. The other was a contract hog producer, but the hog production company decided to restructure and consolidate their business. His production contract was not renewed.

Over the years, Levi had developed many long-term business relationships that spanned decades. Many of these relationships were with landowners who had a high degree of trust in his family. However, times were changing and a new generation of landowners would soon be making their own decisions. Other business relationships were changing too. Suppliers and buyers were becoming larger, and Levi’s business relationships were becoming older. He began to wonder what he could do to be one step ahead of these changing relationship dynamics and the risks they posed for his family business.

Huffman & Hawbaker Farms

Huffman & Hawbaker Farms is a true Indiana family farm. Family has always been a core part of the farm’s success. Levi joined his father-in-law, Ralph Wise, on the farm in 1972. Over the years, his children and their families have joined the farm operation. Levi is the general manager of the farm. His son, Aaron, manages the grain crops and hog operation. His son-in-law, Jim, manages the vegetable crops. There are four other full-time employees. One works in the crop and hog part of the operation, while the other three work in the vegetable enterprise.

By 1979, Levi was farming 1,400-1,500 acres. Now, they operate 3,100 acres. They typically grow 2,650 acres of corn and soybeans and 450 acres of specialty crops each year. They own 15 percent of the land they operate and rent the rest. Around 60 percent of the acres that they rent are built on arrangements they have had for 40 years.

The hog operation also has a long history. When Levi joined the farm, they had a 200- sow farrow-to-finish facility and added a 540-sow farrow-to-finish facility to the hog operation in 1979. The hog operation was very successful in the early years and was the fundamental contributor to much of the farm’s expansion during this time period.

In 1994, the hog house burned down. Reflecting on this, Levi’s wife, Norma, commented “If a building was going to burn down, it is unfortunate that it was the hog facility that was making money at the time. We had been losing money on birds in the poultry facility.” They rebuilt the hog facility in 56 days and continued production, but began to have problems with PRRS outbreaks and market fluctuations. In 1998, they experienced a loss of $40 per hog due to market fluctuations, which led to a large loss in equity. After this experience, they decided to transition to contract production, and now they produce hogs on a production contract with Signature Farms.

Figure 1. Harvesting Tomatoes on Huffman & Hawbaker Farms

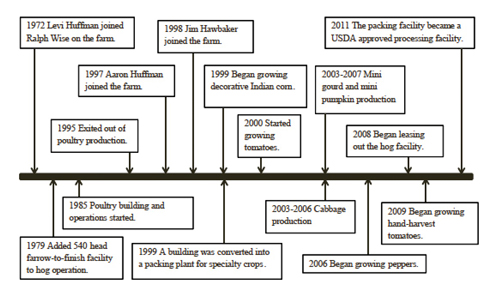

Levi and his family are always experimenting with new enterprises and products to see if they are a good fit for the family’s resources. The timeline in Figure 2 illustrates the number of different ventures that the Huffmans have tried. In the 1980s, they bought ground with a chicken house that would hold 30,000 birds. They also purchased a used building, which raised their capacity to 110,000 birds. In the 1990s, the income from chicken production grew increasingly volatile. In one year, they made $200,000, and they lost the same amount the next year. They exited poultry production in 1995.

Specialty crops have also played an important role in the expansion of the farming operation. In 1999, they decided to transform an existing building into a packing shed for specialty crops. In 2011, they obtained USDA certification for this building. Over the years, they have tried several specialty crops including cabbage, mini gourds, mini pumpkins and decorative Indian corn. The purchasing offer per pound for cabbage was too volatile, causing them to exit this crop in 2006. For the mini-gourds and mini pumpkins, economic conditions at the time indicated that the demand for decorative items would soften. They exited this crop and observed Wal-Mart prices that were $0.12 per item below production costs the next year.

In addition to the hog and grain side of the business, the Huffmans manage 450 acres of tomato and pepper production. Current contracts include arrangements with two different salsa companies as well as a contract with Red Gold. Each processor has a unique contract that the Huffmans are able to use to increase efficiency of the specialty crop venture. One salsa company has more quality specifications than the other. A premium for the higher-quality production can be captured by segregating the production by quality characteristics.

Figure 2. Timeline and History of Huffman & Hawbaker Farms

From careful management of soil nutrients to thoughtful and mutually benefiting contracts with landowners and processors, the Huffmans follow their management philosophy in all aspects of the business. The mission statement of the farm is:

To be good stewards of God’s many blessings, the Huffmans endeavor to produce quality agricultural products by using their abundant resources, preserving the family farm entity while meeting the individual needs of each family unit, offering a helping hand where needed and maintaining a sense of community responsibility while being governed by Christian principles.

In contrast to many Indiana farmers, Levi and his family have chosen to expand their business by focusing on value-added crops. This focus has come from community values, respecting neighbors and not wanting to bid land away from neighboring land owners. Levi says, “Since it is hard to acquire new acreage while still maintaining our goals and mission statement, we strive to increase our return on acres already owned or rented.”

The Risks and the Opportunities

Entering and Exiting New Ventures

Farming has a high level variability and one significant challenge is determining when the outlook for an enterprise is no longer profitable. While remembering his experience with poultry production, Levi says it is important not to “ride a dead horse too long.” The most significant experience of not expanding a venture occurred in 1997. At this time, the Huffman operation had expanded greatly due to the success of the hog operation. When they obtained a hog building permit for 1,200 sows, it seemed like this would be the best way to expand the business. They discussed the option of expanding the hog operation with the family and brought the concept to bankers. After a discussion with their bankers, it became apparent that the expansion would leverage the business too far and the debt-to-asset ratio would be greater than 50 percent. Consequently, they decided not to expand since their leveraged position and risk associated with the return decreased the attractiveness of the venture. The next two years were difficult for the hog industry. Had they decided to expand, the family would have been in a difficult position. Reflecting on this decision, Levi said, “The Lord was looking over us. If a banker would have been more supportive of the investment, we would have gone ahead with the project and would still be experiencing the consequences of that decision today.”

Specialty crops come with their own set of entry and exit challenges. One of the largest risks is changes in market access or purchasing contracts. Red Gold provides a strong base contract for tomato production, which provides flexibility to experiment with other crops. Since market conditions have changed, they are also considering re-entering cabbage production, after their failed venture between 2003 and 2006.

Buyer Relationships

Although the Huffmans could market their grain to Tate and Lyle or other nearby locations, they choose The Andersons as their grain purchasers. Levi uses futures and options as part of his marketing strategy. They store the grain onsite and sell to Delphi or © 2013 Purdue University | CCA CS 2 5 Chalmers, Ind. For soybeans, they also sell to The Andersons. The Andersons take care of the margin money for grain marketing.

When markets are high, Levi typically begins pricing two years before he begins planting. Levi meets with The Andersons once a month and calls several times a week. “I spend more time watching commodity prices than on any other aspect of the farm,” he says.

Due to market fluctuations over the years, Levi says that the farm’s “interest in hogs has waned.” Depending on the death loss rate per group of hogs and current feed prices, the hog operation is leased on a $33-$38 per hog space rate for three years at a time to Signature Farms. The Huffmans also receive the manure as fertilizer, which is around $8 per pig space value when the building is full. Contracts with Tyson, Indiana Packers and other companies required an investment toward facility ventilation. Signature Farms is able to work with the Huffmans with what they have. They are paid quarterly for the 3,050 pig spaces in the building. The Huffmans are responsible for the care of the animals, which includes administering rations, medicines and facility maintenance. They also get paid even if the barn is not full.

The specialty crops are the most work in terms of maintaining the business relationships. Maintaining quality standards, a consistent supply and above-average food safety standards are the three largest concerns. These contracts are written to incorporate quality measures. For example, compensation for peeler tomatoes is based on percent usability that is greater than 80 percent, and percent of tomatoes that are type-A that is greater than 60 percent. Compensation for tomatoes that are used for ketchup is based on color and the percent usable that is greater than 80 percent.

Huffman & Hawbaker’s food safety record programs, operation policies and record logs provide value to their specialty crop customers and set them apart from their competition. A food safety audit form from the USDA is provided in Appendix A. The Huffmans have developed a detailed, 500-page protocol to manage their tomato and specialty crop enterprises to ensure compliance with USDA as well as food safety and quality requirements.

Although there are mock traceback trials to ensure that there are no food safety problems, traceback is still a concern that could damage the farm’s reputation and buyers’ confidence in their products. The Huffmans also create food safety plans to meet new buyers’ preferences. Also, with the specialty crops, the relationship dynamics with the purchaser play a much larger role than in the other enterprises. If problems arise with quality or production during the growing season, proactive communications with the purchaser can dampen any negative responses.

Over time, specialty crop contract relationships have become more demanding. They are long-term relationships but annual contracts. Sometimes, these relationships can be high maintenance, but there is transparency and open communication, which reduces uncertainty. If problems arise, pictures are sent and the problem can be caught more 6 © 2013 Purdue University | CCA CS 2 easily. Some of the relationships require involvement in industry activities that do not necessarily contribute to farm operations. One of these relationships requires attendance from a representative of the farm at growers’ meetings for three to four days throughout the year, as well as time to negotiate and monitor quality and contractual agreements.

Supplier Relationships

For their equipment supplier, the Huffmans are loyal to one brand, due to familiarity. They purchase equipment and parts from Howard & Sons Inc. in Monticello, Ind. They also are loyal to one dealer based on the skills and service of the manager and staff in the parts division.

They have had a connection with their chemical supplier, Crop Production Services (CPS), since 1975. Levi says, “Service is most important and CPS will go the extra mile to help when we need them.” There is a high level of trust in this relationship. For seed, genetics is very important. It is relatively easy to switch between different brands of seed. However, suppliers are tightening contracts to obtain volume discounts and other services — the Huffmans now have 90 percent of their acreage in one brand of seed that the supplier determines. Volume discounts and highly customized service keep this arrangement appealing.

Levi tends to buy all the inputs that he needs for the upcoming year around January 15. Formal contracts with input suppliers are not common. He says, “We are very loyal and stay with supplier relationships unless a problem arises.”

Landlord Relationships

Because of his reputation, Levi’s father-in-law was approached by people in the area and asked to rent their land. These relationships still exist today and are built on trust and a handshake. Levi says “[The owners] trust us and we raise the rent if it’s fair.” More recent rental arrangements have come about through bidding and winning pieces of land. These agreements are built on formal contracts in which the price and terms are more explicitly stated. Their contracts are one-year to three-year cash rent arrangements. Lime is paid for by the Huffmans and prorated over three years if the contract is not renewed. They fix all tile breaks and also cover most of the cost of installing new tiling if these improvements are needed. In the future, they believe that formal contracting will be more common. They are not too worried about losing rented acreage, but believe that a gradual change toward formal contracting is prudent.

The rental land market is highly competitive. There are 17 landowners who lease land to the Huffmans. Of these 17 arrangements, five are formal contracts. Most landlords have a high level of trust with Levi and require little information about the land. The upward pressure on rents and acres transitioning to the next generation of landlords are concerns for this area of the operation. Though the contracts are becoming more formal, the Huffmans still maintain high-quality operations and proof of the maintenance of the soil quality of the land that they rent. They test the soil every three years and always communicate yields.

Lender Relationships

Ten years ago, the Huffmans switched bankers. This change was primarily motivated by the previous bank’s nervousness about the specialty crop venture and their lack of expertise in understanding an organization with a large focus on specialty crops. The current lender does not require titles of the equipment, and a tomato grower is on the board of the bank. The Huffmans have a very open relationship with the lender and are well within the lender’s underwriting standards. They inform the bank about any problems and provide balance sheets, cash flow, income and projected revenue.

Family/Employees Relationships

Figure 3 is the organizational chart for Huffman & Hawbaker Farms. During the busiest months of the year, the business has nearly 120 employees. This includes “professional migrant” workers. The Huffmans use this term to illustrate the value that these seasonal workers bring to the Huffman operation. Because they experienced labor contractors who treated the workers poorly, they no longer outsource the recruiting of temporary labor. The only year that the Huffmans had difficulty obtaining enough seasonal labor was the year that Indiana was considering implementing statewide electronic verification of workers.

Although they take all steps possible to validate the legality of workers, immigration checks are still a threat to operations. Over the years, they have developed a quality labor force and network. Jim Hawbaker views the specialty crop venture as a team effort. Regarding Carlos Hernandez, who is in charge of training, record keeping and human resources, Jim says, “He is very thorough, organized and can handle a lot of stress and not really show it.” They do not worry much about losing long-time employees and are working to achieve a high seasonal labor return rate.

Epilogue

As Levi boarded a plane to head back home to Lafayette, Indiana, he thought about how some of the discussions at the Advisory Board Meeting had reinforced his concerns about the strategic and relationship risks faced by Huffman & Hawbaker Farms. One of the presentations had focused on the potential for reductions in the government safety net for farmers including proposals to reduce the subsidies for crop insurance. These had been critical to their ability to withstand the financial consequences of the drought in 2012.

During dinner with another Board member who had just experienced a financial loss of $250,000 due to trading futures through the mistakes of MF Global Inc, Levi decided that they should devote their next family Board meeting to a more detailed discussion of the risks Huffman & Hawbaker Farms were facing beyond the typical production and price risks and what plans and actions they should consider to manage and mitigate those risks. One of the ideas discussed at the meeting was a risk audit. Levi and his family had experience with food safety audits, but maybe they needed to expand their focus to consider the strategic and relationship risks they were facing.

Key Questions

1. How should Huffman & Hawbaker Farms think about growing their business? How do they create and capture value without taking on more risks than are acceptable and manageable?

2. Should the family incorporate more or less specialty crops into their operations? Does the portfolio of enterprises help manage the risks of the business? Do specialty crops increase the risk?

3. Many of the buyer and supplier relationships of Huffman & Hawbaker Farms are personal with Levi and Norma. When should business relationships be linked more to the institution and less to an individual person?

4. Contract terms and access to markets are key components to specialty crop. What are the risks and opportunities of these specialty crops? How should these risks be managed?

5. As suppliers become larger, what should the family consider about these relationships? How can risks associated with supplier relationships be mitigated?

6. How can the enterprise be more effective in how they approach the next generation of landowners? Are there ways that the vulnerabilities associated with changing landowners can be reduced?

7. Are interest rate changes and financing availability a risk for the operation? How can this risk be managed?

8. What happens if a critical employee is no longer able to work? What are the risks of the current approach of obtaining seasonal labor? How might they manage these risks?

9. How might a risk audit help Huffman & Hawbaker Farms identify the strategic as well as operational risks they are facing? How might it help them mitigate and manage those risks? What risks should they consider as they complete this audit?

Agricultural Economics Department | College of Agriculture | Purdue University

403 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2056, (765) 494-7004

© 2014 Center for Commercial Agricultural, Purdue University | An equal access/equal opportunity university

If you have trouble accessing this page because of a disability, please contact the webmaster at ComAgCTR@purdue.edu